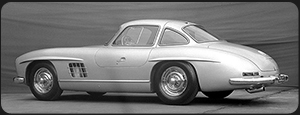

Mercedes-Benz 300SL Coupe

Many 1950s American cars still can turn heads, but they do it with such

things as flashy paint and tailfins. The 1954-57 Mercedes-Benz 300SL

two-seat coupe has a strictly utilitarian design, but still knocks 'em

dead if seen on roads, which isn't often.

Only 1,400 300SL coupes were built, and a really nice one is valued at

a cool $698,000. Most are in top shape because this auto is one of the

most revered sports cars in history and few owners risk driving on

public roads. Even a 300SL coupe in average shape is valued at

$515,000, says the NADA Classic, Collectible, Exotic and Muscle Car

Appraisal Guide & Directory.

The 300SL coupe's flip-up doors may seem gimmicky. But the car was

derived from a famous early 1950s Mercedes sports/racing car and

conventional swing-out, full-height doors would have hurt rigidity of

the complex, multitube space-frame chassis--a Sports Light (SL) race

design that minimized performance-robbing weight.

The half-height doors, hinged at the roof center to lift upward, led

the 300SL to be nicknamed "Gullwing" because the car resembled a gull

with its wings raised when the doors were up. Flip-up doors later were

copied by the DeLorean and Bricklin sports cars.

The 300SL has never gone out of style. Men's Journal magazine named it

one of the 25 greatest cars ever made and said it "still looks better

than most cars on the road." Automobile magazine's founder called it

one of the "20 most beautiful cars of the last 100 years."

The Gullwing's styling is so good that you couldn't change a body line

without causing its appearance to suffer. Beauty was more than skin

deep. For instance, this was the first production car to use fuel

injection, which most autos wouldn't offer for decades.

How did a race car not conceived as a road car come to be produced?

Thank Max Hoffman, who was the influential U.S. distributor for many

European cars when they were new to America in the 1950s. He convinced

Mercedes that a road version of its race car would be a hit.

It was a different auto world in the 1950s, when Hoffman also convinced

BMW to build the gorgeous 507 sports car and Porsche to build its slick

Speedster two-seater for the U.S. market. Both cars now also are

high-priced classics.

New York-based Hoffman was a former European operating in an America

still dazzled by sports cars. He backed his words to Mercedes by

ordering 1,000 of the production 300SL coupes.

That order was enough to convince Mercedes to build the Gullwing. It

was suffering from World War II damage and needed money. It also wanted

the pre-war glory it had enjoyed.

Few Americans outside of a relative handful of foreign car buffs knew

about the winning race cars that led to creation of the 300SL coupe.

But the car surely promised to put Mercedes on the map in America, if

any car could.

The 300SL coupe debuted at the New York Auto Show n February 1954 and

was an instant sensation. It soon became the ultimate auto status

symbol, bought by celebrities and prominent movie stars such as Clark

Gable. Even the few largely hand-built Ferrari road cars, which really

weren't production autos, couldn't match its charisma.

Mercedes had no money for major new components, so the Gullwing used a

modified 240-horsepower version of its 3-liter inline six-cylinder

engine from the fairly new Mercedes 300-series sedan. Other major items

taken from the 300-series were a rugged transmission and suspension.

High, wide door sills made it difficult to get in and out of the

Gullwing, although a tilt steering wheel allowed easier entry and exit.

Windows were snap-in units because there was no room in the doors for

roll-down windows. There was a flow-through ventilation system instead

of air conditioning, which simply wasn't considered in an auto derived

from a race car.

I nearly fried while driving a friend's 300SL coupe on a hot summer day

with the windows in place, although speeds were high on nearly deserted

two-lane roads. The car's owner said the windows were a pain to remove

and put back, and I only drove the car about 75 miles.

The Gullwing wasn't far removed from the Mercedes race car, which had

virtually no sound insulation. The snug, businesslike cockpit thus was

full of engine and transmission noise. Steering was quick, and the ride

was surprisingly supple. Braking was strong.

The Gullwing was fast partly because it was highly aerodynamic. For

example, its engine was tilted 45 degrees to allow an especially low

hood line for less wind resistance, which was highly unusual at that

time.

The 300SL coupe cost about $7,000, or approximately as much as a

Cadillac limousine. It could hit about 160 mph with the right gearing.

But most Gullwings sold here were geared to do about 130 mph to allow

faster acceleration for under-100 mph American driving conditions.

All-aluminum competition bodies could be ordered, as could handsome

custom-fitted luggage for the area directly behind the supportive

bucket seats. A big spare tire filled the trunk.

The Gullwing was virtually indestructible--one reason it beat more

powerful cars such as Ferraris in races. Rugged and brilliantly

engineered, you could drive the 300SL coupe all day at top speed if

roads were clear.

The faster I drove the Gullwing, the happier it became. It was docile

at low speeds, except for heavy steering that didn't lighten up until

the car reached about 45 mph--typical for high-speed sports cars then.

Sales of the 300SL coupe never were high because it was expensive and

impractical for even most sports car buffs. A heavier, more comfortable

300SL convertible was introduced in 1957 with a modified frame that

allowed conventional doors with roll-down windows.

Americans more readily accepted the 300SL convertible, which lasted

until 1963 and outsold the 300SL coupe, drawing 1,858 buyers. The

convertible now is valued at $585,600 if in excellent condition, or

$449,600 if in average shape.

In the end, though, there's no matching the Gullwing for its heritage

and sheer excitement.